Review: Exodus (by Brian Wildsmith)

A beautiful and faithful retelling of the Exodus story

As a father and a theologian, I have opinions about children’s Bibles and Bible stories. In my view, good children’s Bibles should help children learn, enjoy, and explore biblical stories—not only teaching the main ideas and general plot, but also drawing them into the details and language of the Bible. The best do the same for adults! (Reading children’s Bibles does not have to be painful or mind-numbing.)

A few weeks ago I reviewed one of my favorite New Testament children’s books, Who Counts? by Amy-Jill Levine and Sandy Sasso. Here I review one of my favorite retellings of an Old Testament story, Brian Wildsmith’s Exodus.

If after reading this review you’re interested in buying this book, please consider supporting my work by using the Amazon affiliate links on this page.

Do also have a look at my study questions about next week’s lectionary reading, Luke 17:11-19 (the ten lepers).

Overview

Text: Exodus 1-17, 19-20, 32-34, Deuteronomy 34

Age: 4+

My Rating: 👍

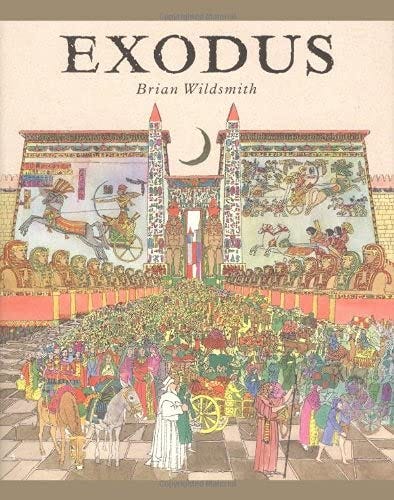

Exodus by Brian Wildsmith (1998) is a faithful retelling of the story of Israel’s exodus from Egypt, gently emphasizing the theme of liberation. It is beautifully illustrated in a style reminiscent of classical Egyptian painting. The plain storytelling and exquisite pictures capture the imagination of my 3-year-old. This is by far my favorite children’s version of the exodus. I highly recommend it!

1. Story

Exodus retells the whole exodus narrative in only 32 pages. We hear (among other things) of the birth of Moses and his killing of the Egyptian guard; the burning bush, the plagues, and the Passover; the parting of the Red Sea and Israel’s grumbling; the ten commandments, the golden calf, and God’s forgiveness; Moses’ death and the people’s entry into the land under Joshua. This is a lot of material to cover, but with Wildsmith’s brisk narration it never becomes tiresome.

Like most of my favorite children’s books, Wildsmith endeavors to preserve the distinctive literary quality of Biblical narratives, particularly their succinct realism.1 Wildsmith's telling of the exodus is straightforward and open-ended. He is not anxious to draw moral or theological lessons, leaving space for imaginative play, discussion, and questioning. Of course the Bible teaches moral or theological lessons; but the way it is written also has much to teach. Precisely because the Bible is difficult and invites reflection, it trains us to interpret human events and human language in all their complexity and ambiguity.2

Of course, every retelling has its own angle. Wildsmith’s Exodus gently emphasizes the theme of liberation. The first pages focus on the cruelty of Egyptian slavery. The story ends with a summary that echoes Martin Luther King Jr.’s use of the old spiritual, Free at Last:

After all their wanderings and struggles, they were a free people at last. They had finally come home.

The bulk of the story displays enough of the grandeur of Egyptian civilization and the violence of the exodus to underscore just how difficult and remarkable was Israel’s deliverance from slavery, and by implication, how great and good the God who could accomplish such a marvel.

Yet Wildsmith’s telling also preserves much of the rich texture of Biblical language. For example, Wildsmith’s account of the burning bush judiciously incorporates many phrases directly from the scriptures: “God appeared to him as a fire blazing out from a bush. Although the bush was on fire, it was not burned up.” (3:2), “Take off your shoes, for you are standing on holy ground” (3:5), “a land flowing with milk and honey” (3:8). He borrows a summary of the Passover ritual from Exodus 12:8: “they roasted the lamb, ate it with flat bread and bitter herbs.”3 We learn that Pharaoh went after the Israelites with chariots (14:7).

Wildsmith says that the pillars of cloud and flame kept “the two armies” of Egypt and Israel apart. Calling the Israelites an “army” so surprised me that I had to look it up. Sure enough, Exodus 14:20 refers to the “camp” of Egypt and the “camp” of Israel, using the word “machaneh” (מַחֲנֵה) which frequently denotes an armed encampment or an army (Joshua 6:11, 8:13, and many other places in Joshua - Kings). Although we often think of the Israelites as a motley and relatively powerless band, it is worth considering whether God has to tell the Israelites, as the Egyptians are bearing down upon them, that “I will fight for you!” (14:14) precisely because they would otherwise be tempted to pick up weapons and fight!

There are many other examples of Wildsmith’s fidelity to Biblical language. The upshot is that kids who remember and ponder this version of the story will frequently be engaging with the words of the Biblical text. This is something for parents and teachers to embrace, especially as older kids begin asking more questions about the details of what you’re reading. You may not know how the land was “flowing with milk and honey,” or why this band of Israelites is called an “army.” But many fruitful insights may occur to you and your children as you talk about it together. Those who learn to love scripture most deeply are usually those who come to love the way its difficulties draw readers into its depths.

2. Artwork

Brian Wildsmith is also an award-winning artist, and his illustrations for this book are simply gorgeous. Since his death in 2016, his children have put a lot of his work online—definitely worth a peek. He has illustrated many other Bible stories (including Joseph and the Easter story), and a posthumous children’s Bible featuring his images was also recently published.

In Exodus, Wildsmith’s intricate illustrations take their cue from classical Egyptian artwork. Compare, for example, this piece of classical Egyptian painting:

with Wildsmith’s depiction of Moses before Pharaoh’s court:

These images lend an Egyptian flavor to this story, even as they give a powerful sense of the grandeur and greatness of Egyptian civilization. (This makes all the more stark, of course, Egypt’s cruelty towards the Hebrew people and the greatness of Israel’s God.)

His illustrations are drawn with minute detail, from intricate wall paintings to vast crowds of individually-drawn figures. My son loves the many animals that pop on page after page: Pharaoh’s daughter’s pet dog (!), Moses’ flock, the leopard beside Pharaoh in the photo above. Wildsmith’s pictures also display the vibrant colors of the ancient Mediterranean world. We are liable to forget how colorful that world would have been, since little remains of it for us besides the monochrome ruins of ancient buildings and statues whose paint has long since faded.

Wildsmith’s illustrations also provide useful interpretive guidance. The pillars of cloud and fire, for example, are juxtaposed, helping children grasp their parallel function. Both are also painted so as to suggest hands, pointing the people onward. His picture of the manna falling gives it the look of snow, and some of the Israelites are dancing joyfully in it like children in the snow. The giving of this bread from heaven, Wildsmith implies, is cause for great joy. By contrast, Sinai is depicted ominously as a fearful volcano: no wonder that Moses says, “you were afraid because of the fire, and you did not go up the mountain” (Deuteronomy 5:5). He depicts Moses in the act of throwing the tablets of the covenant on the ground, fully of fury, as Aaron begs for forgiveness and Joshua covers his face in horror. Thus we learn the range of responses warranted by flagrant sin.

3. Exegesis

The best children’s books encourage adults as well as children to meditate on scripture. One way to engage in this is by observing the exegetical decisions their authors have made, reflecting on their reasons, and asking whether the story might be told differently.

Sometimes Wildsmith adds little details mainly to clarify or embellish the narrative. When the Israelites grumble in the desert, it is because “the sun beat down on them,” a description that helps kids understand what it means to live in a desert. Wildsmith helpfully glosses what is at stake in the Israelite’s demand for the golden calf: “Make us another god, a god that we can see.” The Israelites do not say “a god that we can see” in Exodus 32, but it is an apt summary of what they are seeking. (Wildsmith himself tactfully represents God’s presence as a six-pointed star, wisely avoiding the illustrator’s temptation to make an image of God.)

Wildsmith also frequently supplies motivations for the characters. The book of Exodus does not tell us why the Israelites demand a golden calf, but Wildsmith adds that they “grew angry and impatient.” Maybe so. But perhaps they were bored, or perhaps they were motivated by a (misguided) desire to worship the God who rescued them from Egypt? When the angel of death passes through Egypt, Wildsmith explains that their “great cry” (Ex. 12:30) was “a cry of grief for their dead sons.” Very likely. But perhaps it was also a cry of bitterness at Pharaoh, or of anger at the Israelites?

Moses, we are told, “hated the cruel way his people were treated.” But Exodus says only that, when he was grown, he “looked at” the burdens of his people (2:11). Sometimes the word “look” can imply a realization—could it be that, until that point, the cruelty of slavery had never occurred to him? Similarly, we are told that he killed the Egyptian guard because he “was so angry.” But the text never says this, and the fact that Moses took a look around (2:12) could imply a greater degree of premeditation. (The movie Prince of Egypt narrates these events rather differently, and is worth inviting older children to compare them.)

An interesting expansion occurs not in the written text but in the illustrations. Wildsmith depicts a pair of angels holding trumpets atop Mt. Sinai. No angels at Sinai are mentioned in the book of Exodus, but several New Testament writers claim that angels played the role of mediators of the Law.4 The presence of angels at Sinai was also a well-established Jewish tradition.5 One source for this tradition seems to have been the poem Moses spoke near the end of his life. Deuteronomy 33:2 says:

The LORD came from Sinai…He came with ten thousands of saints;

From His right hand came a fiery law for them.

Who are these myriads of holy ones that came with the LORD to gave the Law? The Hebrew phrase translated “fiery law” (אֵשׁ דָּת) is odd and the text difficult. Perhaps relying on a variant text, the traditional Greek translation instead clarifies the identity of these holy ones: “From his right hand, angels were with him.”

Another noteworthy expansion comes near the end. After seeing the promised land from the distance and dying “in a peaceful valley,” we are told that “the people buried him.” He is retelling Deuteronomy 34:5-6, which says that Moses died “according to the word of the LORD. And he buried him…” Who buried Moses? The verb is singular, and the most recent antecedent is “the LORD.” The implication is that God himself buried Moses (probably giving rise to the curious tradition, mentioned in Jude 1:9, that the devil argued with the archangel Michael about Moses’ body). This also explains why “no one knows his burial place to this day.” (Dt:34:7). Wildsmith’s reading is attractively less supernatural, but it requires taking the “he” of verse 6 as the people of Israel—not impossible, but linguistically strained.

If you examine Wildsmith’s expansions with your Bible open, they invariably reward reflection. Especially with older children, it will be fruitful to ask why Wildsmith told the story this way, and whether it might be possible to fill in the details differently.

Wildsmith also omits a lot of detail, as any children’s book must. We hear nothing of Moses’ attempt to meddle in an argument between two of his kinsmen. His whole time in Midian is telescoped down to one sentence, omitting his rescue of Zipporah’s sisters from the well and of his marriage to this foreign woman. There is no mention of the sabbath or of the tabernacle. The only laws mentioned besides the Passover are the ten commandments, described as laws that “told the people how they should live.” (The Ten Commandments are enumerated in the front and back covers, together with an elegant depiction of the ark of the covenant—but in an annoying paraphrase.)

In part because of these omissions, Wildsmith’s version downplays some important themes. Two in particular stand out to me. First, there is no mention of God’s covenant with Israel. In Wildsmith’s telling, God’s laws tell the people how to live, but there is no indication that this way of living is desirable because God binds himself to Israel through his promises, as e.g. in Exodus 19:5-6:

Now therefore, if you will indeed obey My voice and keep My covenant, then you shall be a special treasure to Me above all people; for all the earth is Mine. And you shall be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.

Second and relatedly, there is little mention of worship. In the book of Exodus, God frequently repeats the refrain, “let my people go, that they may worship me in the wilderness.” (7:16 et al.) The drama of the passover story is interrupted for several chapters about the Passover; the instructions for building the temple take up a third of the book (chapters 25-31, 35-40). Certainly in Wildsmith’s telling we hear of Moses’ intense encounters with the living God, and we see God’s presence with Israel in the form of the cloud and pillar of fire leading Israel to freedom. But there is no indication that the upshot of these events is that God will dwell in Israel’s midst. In short, one might wish that this telling made more of the way Israel is liberated to be God’s people.

4. Conclusion

The overall question I ask when recommending a children’s Bible is whether it will reward rereading. In this case the answer is clear: my three-year-old continues to find this version of the exodus captivating, and it keeps challenging me as well. Brian Wildsmith’s Exodus is one of the best children’s Bible stories you will find. 👍

If after reading this review you’re interested in buying this book, please consider supporting my work by using the Amazon affiliate links on this page.

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

If you’re interested in the poetics of Biblical narrative, you could read Erich Auerbach’s classic Mimesis, Meir Sternberg’s difficult The Poetics of Biblical Narrative, or James Kugel’s The Bible as it Was, which shows how Biblical poetics gives rise to classical Jewish and Christian interpretation.

By all means teach your child to see how the Exodus story points to Christ, or how it directs us to work for the liberation of the oppressed—but do this by talking with them about the details of the story. Don’t identify your own human insights (however profound or true) with the Bible itself; and don’t suppose that only “conservatives” are guilty of doing this!

These are the same three elements that Rabban Gamaliel identifies as the core obligations of Passover, a teaching which is recited as part of the traditional Jewish seder meal.

Gal. 3:19, Acts 7:38, 53, Hebrews 2:2.

See Jub 1:29, Antiquities 15.136, Pesiq. Rab. 21.7-10.