The Sabbath as Hermeneutic Teacher

Three commonly neglected principles of legal interpretation

First, another bit of news: this Sunday morning we baptize our daughter Geneva, formally receiving her into the household of God. We will commit ourselves to help her grow into the full stature of Christ. May all of you whose lives intersect with hers do the same.

One of the central themes of my forthcoming book is that the Sabbath—given to Israel while still on the way to Sinai—can be understood an introduction to the Law. In this week’s newsletter, I reflect on some hermeneutical lessons we can learn from the Sabbath. Studying and practicing the Sabbath can help Christians become wiser interpreters of the whole Law—which can, in turn, help alleviate some of our deep and recurring anxieties about the Law.

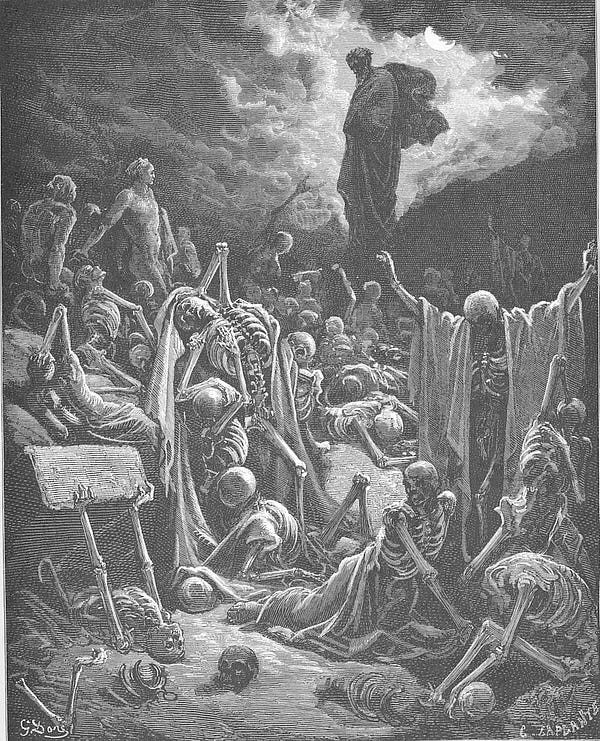

I also hope you’ll have a look at my study questions and commentary and next week’s lectionary gospel reading (Luke 20:27-38), Luke’s version of the dramatic moment in which the Sadducees ask Jesus a “gotcha” question about the resurrection that turns on the Biblical practice of levirate marriage (Deuteronomy 25:5-10). In my questions and commentary you’ll find reflections on marriage and the nature of our resurrected life, and even patristic speculations about whether the resurrection of the body might involve a sex change!

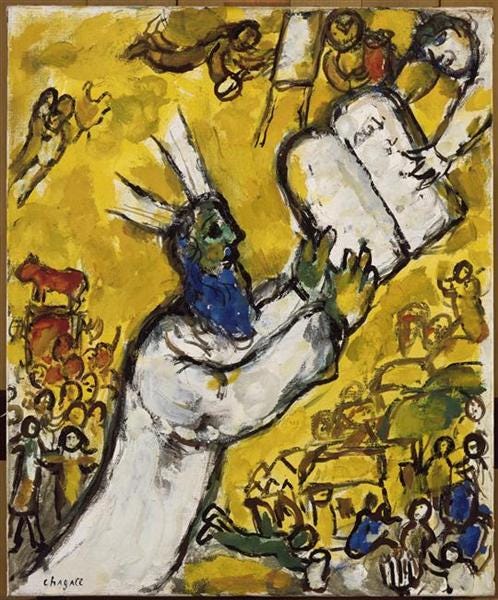

Although the Sabbath is one of the Ten Commandments, it was given to Israel before the rest of the Law, while still on the way to Sinai (in Exodus 16). I believe the Sabbath was given before the rest of the Law, in part, because the Sabbath was Israel’s introduction to the Law. The Sabbath introduces the Law in many ways: by helping Israel to acquire a taste for the Law’s notion of freedom; by summarizing its essence in a single concrete practice; by creating time for study and reflection on the Law.

I want to focus on another: the Sabbath introduces the Law by teaching, in an especially clear way, some key but often neglected principles of legal interpretation. Here are three examples. First, Christians often believe that we should interpret the Law by asking about the purpose of a command. We assume (not unreasonably) that a law is binding only so long as it continues to serve its purpose. If the purpose of the dietary laws were to maintain the health of the people, for example, then one might suppose that modern medicine should make such laws obsolete. This principle can also be applied to the Law as a whole: if Christ is the goal of the Law, it might seem that the coming of Christ should also bring the Law to an end. If all the Law hangs on the twin love commands, it might seem that knowing this frees the Christian to disregard any law that does not obviously advance love.

Thinking about the purpose of a law can be fruitful. But it is a mistake to assume that a given law has only one purpose. The God who created such marvelous diversity in the world might also give laws with a plurality of purposes, some of which might remain as yet undiscovered. The Sabbath displays God’s plurality of purposes quite explicitly. The Sabbath is given as a testimony that “in six days the Lord made heaven and earth and sea, and all that is in them, and He rested on the seventh day” (Exodus 20:11). It is a reminder to Israel that “you were a slave in the land of Egypt and that the Lord your God freed you from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm” (Dt 5:15). It it is given for the sake of rest and refreshment, “that your male and female slaves may rest as you do” (Dt. 5:14). It is a kind of public testimony like a wedding ring, “a sign between Me and you throughout the ages, to know that I the Lord have sanctified you” (Ex. 31:13). Christians would add that the Sabbath also points to Christ and to his kingdom, “a shadow of things to come, whose substance is Christ” (Col. 2:17).

The Sabbath has these five purposes; perhaps it has more. And what is true of the Sabbath may be true of other commands, and of the whole law which the Sabbath introduces. But for this very reason, we may not assume that a command can be reduced to or replaced by its purpose. Perhaps one purpose has outlived its utility—can we be sure that all have? We must be slow to assume that changing circumstances or fulfilled purposes have made a law obsolete.

Second, laws need not be clear or rigid. Like the laws of creation, they may be open-ended or vague, requiring wise readers to discern unstated exceptions. Most legal systems take pains to remind lawyers of this, particularly when interpreting general rules. Jewish sages express the principle this way: “we infer nothing from general rules.”1 The rabbis called general rules kelalim, from the word “all” or “every” (kol). General rules are often expressed as statements about “all” or “every” member of some class; and yet as the great medieval jurist Maimonides says, “when it says ‘all’ it really means to say ‘most.’”2 This is not as paradoxical as it sounds: when we say “a watched pot never boils,” “never” does not really mean never!

One may not draw inferences from general rules because they tend to have unstated exceptions or implicit expansions. Consider the Sabbath command in the Decalogue, formulated as a general rule using the word “all” (kol):

The seventh day is a sabbath of the Lord your God; you shall not do any [kol] work… (Ex. 20:10)

Let us set aside the vagueness of the word "work" and focus on the unstated exceptions to this rule. Some are stated explicitly in other contexts. Although kindling a fire is undoubtedly work (Ex. 35:1), there is an implicit exception for the priests, who are commanded to offer burnt offerings on the Sabbath (Numbers 28:9-10). Circumcision is presumably a kind of work; yet since the law commands it be done on a specific day, the eighth (Lev. 12:3), one might reasonably infer (as the rabbis did) that the work of circumcisions should be performed even on the Sabbath.3 Other exceptions are implicit and require greater wisdom to discern. For example, the rabbis carved out a major exception: one should violate the Sabbath if there is the slightest risk to a person’s life, the principle of pikuach nefesh.4 Jesus echoed this principle and expanded it to include healing of any kind on the Sabbath. Jesus' practice does not mean he was disregarding the Sabbath, and more than the rabbis did. Rather, Jesus understood that a general rule, though it use the word "all," cannot be assumed to apply in every circumstance.

A third error Christians often make is to think about laws instrumentally, as unpleasant means towards some desirable end outside the command itself. We often approach law as a child might submit to eating politely in order to get desert after dinner. She doesn’t care about politeness—she just wants desert! But of course ultimately parents want children to outgrow this instrumental attitude, to learn to follow the rules for their own sake—those rules, I mean, which are really worth following. According to Paul, the law is a “teacher” (Gal. 3:24). If it begins by motivating us instrumentally, restraining our sinful desires through external rewards and punishments, its goal is to teach us to love the Law for its own sake, so that in the end, “perfect love drives out fear” (1 John 4:18). We learn to say with the Psalmist:

The law of the Lord is perfect, reviving the soul;

the decrees of the Lord are sure, making wise the simple;

the precepts of the Lord are right, rejoicing the heart;

the commandment of the Lord is clear, enlightening the eyes;

the fear of the Lord is pure, enduring forever;

the ordinances of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.

More to be desired are they than gold, even much fine gold;

sweeter also than honey, and drippings of the honeycomb. (Psalm 19:7-10)

For indeed we should want to become the kind of people who not want to commit adultery or even cultivate lust in our hearts—even if we could get away with it. We should not want to commit murder and cultivate anger in our heart, or to steal and oppress the poor. To be this kind of person is to love “thou shalt not commit adultery,” “thou shalt not murder,” and the rest for their own sake.

In rejecting “salvation by works,” Christians reject an instrumental view of the Law—it is fruitless to obey the Law as a means to salvation. But Christians often forget that as Israel was saved into a kingdom governed by God’s Law of liberty, so we are saved into the kingdom of God, a kingdom ruled by the good and just law of Christ. The law is not a means to salvation; rather, it defines the character of the kingdom into which we would be saved. This is why it is senseless to ask “shall we sin, that grace may increase?” (Romans 6:1). The question supposes that sin would be good and desirable in itself, if only we were allowed to pursue it. But as Paul insists, it was sin that killed us, and sin that Christ’s death aims finally to kill. “How could we go one living in sin?” Sin is the very thing we want to be free from!

The Sabbath can help teach this too. It too is a commandment of the Law, but it is one whose goodness is especially manifest. Given to Israel while still on the way to Sinai (Exodus 16), the Sabbath helped this newly-liberated people, bearing still the fresh wounds of slavery, to trust the goodness of her liberating God and of the Law that this God puts forth as freedom. Those who keep the Sabbath and experience it as good and live-giving can more easily imagine how the whole Law could also be a life-giving gift. No wonder the prophet Isaiah could call the Sabbath a day of “delight” (Isaiah 58:13).

b. Kid. 34a.

Commentary on the Mishnah, ad m. Kid. 1:7.

For example, m. Shab. 19:3.

For example, b. Yoma 84a-85b.

I agree with your point that it's not necessarily a great idea to think of the laws instrumentally.

I wrote a post about the benefits of observing a Sabbath and I'm curious for your perspective! https://trailblazingtwenties.substack.com/p/a-power-of-sabbath-time-blocking