This week I review a version of the book of Jonah illustrated for children by a remarkable Georgian Orthodox artist named Niko Chocheli. (Having lived for several years in nearby Azerbaijan, I have a special fondness for all things Georgian!)

With Christmas on the horizon, you might look again at my previous reviews: Exodus by Brian Wildsmith, Stilling the Storm (Jesus calms the sea) from the Tiny Readers series, and Who Counts? by Amy-Jill Levine and Sandy Sasso (based on Luke 15). And watch this space: in a few weeks I’ll post a review of my favorite telling of the Nativity!

You’ve probably noticed that I’ve been using Twitter as a venue for posing exegetical questions about the lectionary, in the spirit of classical catena commentaries. This week’s commentary—on Luke 23:33-43—raises rich questions about the meaning of Christ’s death and the nature of true repentance. You may also be surprised to learn, as I was, that the famous words “Father, forgive them, they know not what they do,” are missing in some of the best early manuscripts.

This brings my Twitter commentary to the end of the liturgical year. By coincidence or providence, we may also be nearing the end of Twitter. So it’s a good opportunity to consider whether and how to continue. If you’ve found this a helpful resource—or if you would be more likely to use it on a different platform—could you let me know in a comment or an email?

Text: Jonah

Age: 4+

My Rating: 👍

The Book of Jonah by Nico Chocheli is a challenging but compelling version of the Biblical tale that includes every word of the text according to the Revised Standard Version. The gorgeous illustrations inspire a sense of wonder appropriate to the grand scale of the story. Despite the difficulty of the language and the length of the text, I find that it not only captures the imagination of my three-year-old but challenges me as well.

1. Story

This book tells the story of Jonah, the prickly Israelite prophet who refuses to “cry against” Nineveh because of its wickedness, fleeing instead to Tarshish. Finally, after three days and three nights in the belly of a great fish, Jonah acquiesces, only to find that the Ninevites repent of their sins and God relents of his punishment. The story ends with God’s unanswered question—to us, as to Jonah—”should I not pity Nineveh”? (4:11) This dramatic story has always been a favorite with children. But underlying the action are potent (and very adult) lessons about the need for obedience and faith, about God’s providence and grace for various kinds of sinners (Ninevites, of course, but also stubborn prophets), about the reach of God’s love beyond ethnic and national boundaries, about the possibility and the offense of repentance, and about the obligation to love and be gracious even to our enemies.

Chocheli’s version is noteworthy because it is neither a retelling of Jonah nor a paraphrase. Rather, it contains the entire book of Jonah, and what’s more, in a fairly demanding translation, the Revised Standard Version. Many adults probably imagine that it would be impossible to sit down and read four chapters of the Bible to a child in a single sitting. Chocheli’s edition of Jonah is a powerful counterexample. I find that—in part because of its exquisite illustrations (see below)—his The Book of Jonah can hold the attention and spark the imagination even of a three-year-old, especially if read confidently in a lively spirit.

It’s worth reflecting on the very adult anxieties that might make us shy away from a difficult book like this. First: how can a young child take in an entire book of the Bible, four chapters, in a single sitting? Perhaps with most books of Biblical narrative this would be impossible. Longer Biblical narratives tend to be comprised of shorter episodic stories that circulated in an earlier oral or written form. There is a definite plot to the life of Jacob, or David, or Jesus for that matter—but it can be hard to discern amidst the hodge-podge of individual episodes that comprise them. (The Bible often seems blithely unconcerned with Aristotle’s tidy counsel that a story ought to have a beginning, a middle, and an end!)

Jonah, by contrast, is a short and tightly-crafted linear narrative. It unfolds in four clear acts:

Jonah’s disobedient refusal to preach to the Ninevites;

his repentance inside the great fish;

his obedient willingness to preach to the Ninevites; and

his renewed resistance to God, after God accepts the Ninevites’ repentance.

These four acts also thematically correspond to one another. Jonah’s obedience in chapter 3 corrects his initial disobedience in chapter 1. Likewise his bitter resistance to the Ninevites’ repentance in chapter 4 corresponds to his own need for repentance in chapter 2, bringing the whole story full circle. This careful plotting makes the book of Jonah especially easy to tell and to hear in a single sitting, even for children.

Jonah is also an especially exciting story, full of adventure on the high seas, a vomiting fish, a great king, and a persistent worm. It has a larger than life quality. Everything in the tale is especially “big” or “great”: Nineveh is that “great city” (1:2), God sends a “great wind” and a “mighty tempest,” (1:4) the mariners were “exceedingly afraid” (1:10), God sends a “great fish” (2:1), Jonah is “very angry” (4:1), “very glad” (4:6), and so on. The English translators have varied the adjectives, but in Hebrew it is the same in each case: gadol, “great.” This pattern is a clue (there are others) that what we are reading is a “tall tale” or a “fish story”—not a sober retelling of historical events but a compelling fiction designed to entertain as well as teach. And so it does, if we let it.

Second: can children really manage a difficult translation like the Revised Standard Version? The RSV is a revision of a revision of the King James Version (which was, in turn, a revision of Tyndale’s groundbreaking translation). Intentionally positioning itself in this King James tradition, it retains many echoes of the KJV’s grand Elizabethan English. It uses some archaic terms: the sailors are “mariners,” the storm a “tempest.” While it no longer uses the archaic second-person singular (“thou”/”thee”/”thy”), it retains them the context of prayers, like the second chapter of Jonah. The RSV also shares the KJV’s word-for-word (or “formal equivalence”) translation philosophy, leading to some difficult constructions. For example, when Jonah is pouting outside the city, God asks him, “Do you do well to be angry?” (4:4, 9—following the KJV: “Doest thou well to be angry?”) This is close to the Hebrew: the main verb is related to the word tov, good, and means something like “do well” or “do good.” Most modern translations translate the sense more naturally but also more narrowly: “is it right for you to be angry?” (NIV)

There’s no question that this translation is challenging to adult ears. But it’s a mistake to assume that young children experience its language the way we adults do. Adults have a large and relatively settled vocabulary, in light of which we hear certain words as “difficult” (because we use them more rarely) or “archaic” (because we recognize them as old-fashioned). We can afford to resist difficult or archaic language—which, if we are honest, is mainly resistance to learning. Translations, we suppose, ought to cater to our linguistic conventions as they are, rather than stretching or expanding the way we speak.

Whatever the merits of this approach for adults, it makes little sense when applied to children. All words are new to children! They are constantly hearing words they don’t know, unavoidably thrust into the posture of learning new words. What’s more, they are exceptionally good at it. One of the great mysteries of human nature is how quickly and almost effortlessly young children can assimilate language with surprisingly little formal instruction. All this would not be possible if children shared our very adult resistance to difficult language. On the contrary: children enjoy learning language! (Anyone who has seen a child delight in a great poem—the Jabberwocky, say, or The Lorax—will know what I mean.)

When we read a book aloud, including a book of the Bible, much of what we are doing is teaching children its language. But it can make little difference to a child—already accustomed to learning new words—whether you say “storm” or “tempest,” “you” or “thou.” I found that when reading The Book of Jonah to my three-year-old, it was enough just to tell him that “a mariner is a sailor,” “a tempest is a big storm,” and to reinforce this lesson by pointing and by spirited reading. The actions and illustrations help children interpret the words they are hearing.

That said, the poem-prayer that occupies chapter 2 is more difficult than the rest of the book. The problem is not that the RSV retains the archaic second-person plural in its prayers. These forms are easily learned. (At least in our family and church, we still use these them in the context of the Lord’s Prayer: “Our father who art in heaven, hallowed by thy name…”) Nor is it exactly true that the prayer lacks action. Much of it in fact narrates the dramatic experience of sinking into the sea:

The waters closed in over me,

the deep was round about me;

weeds were wrapped around my head

at the roots of the mountains. (2:5)

But the prayer’s primary concern is with the movements of the repentant soul, and these are more difficult to grasp than corporeal events in time and space. Moreover, Jonah expresses his repentance in the language and imagery of ancient Israelite temple worship: “my prayer came to thee, into thy holy temple…I with the voice of thanksgiving will sacrifice to thee…” (2:7, 9) for which modern children have very little point of reference. Nor is it easy to explain to a child what it means to pray “Those who pay regard to vain idols forsake their true loyalty.” (2:8) (I find that my son struggles most in these sections of the book.)

There remains value in exposing children to the words of scripture, which are seeds that can bear fruit later as understanding. When reading a difficult book like this, if you can read through all the words without losing a child’s attention, do it. But it’s perfectly legitimate to omit harder sentences as you read aloud, and return to them later when your child is older.

2. Art

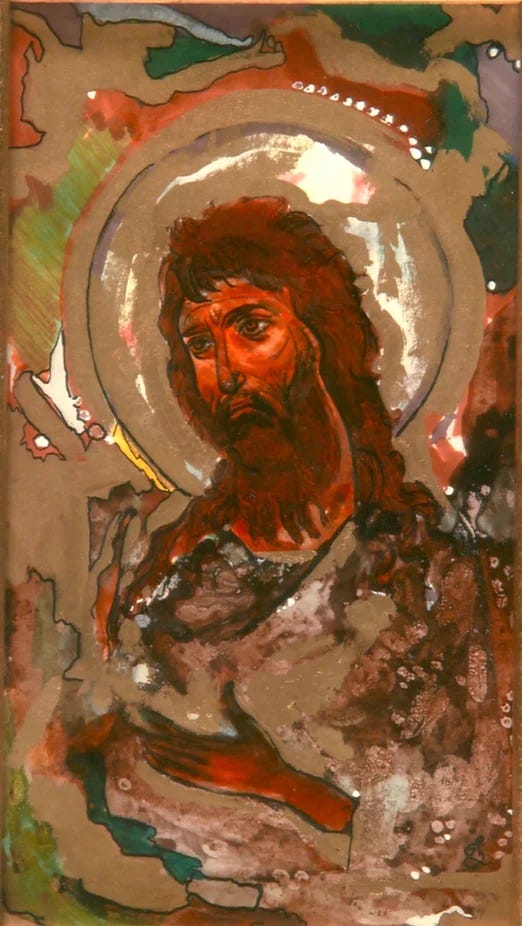

If this story holds the attention of young children, it is in no small part because of the gorgeous artwork by Niko Chocheli. Chocheli is a Georgian Orthodox artist with a concentration in Orthodox iconography. His work often combines realistic depictions of human faces reminiscent of icons and of the Old Masters with more abstract or fantastic elements. Some of his icon-inspired paintings visible online are especially beautiful:

He has illustrated three other children’s books: the litany of praises in Psalm 148, a Christmas book of biblical texts interspersed with Orthodox liturgy, and a collection of prophetic Old Testament texts. These books are all published by St. Vladimir’s Press, an Orthodox publisher.

Chochelli’s exquisite illustrations are hard to describe. They combine ink sketches with watercolor, using the intensity of the color to highlight important events or objects. Chocheli has created luxurious underwater scenes, with expressive fish faces and brightly colored sea creatures; my son loves to stare at them. Nineveh is a vibrant and colorful Middle Eastern town in the distance, as a somber Jonah approaches. The will of God is suggested by a giant hand, pointing the way to Nineveh, emerging out of the tempest to overwhelm the boat. The great fish—depicted as a humpback whale—dwarfs poor Jonah being tossed into the sea. (In the cropped image below, you can just see Jonah’s feet as he tumbles into the water).

One detail puzzled me at first: from the time Jonah is vomited out of the great fish to the end of the book, Chocheli places a magnificent peacock feather in his cap. The likely reason, a bit of research revealed, is that the peacock was an ancient Christian symbol of immortality. It was also associated with Jonah from a very early period. There is, for example, a remarkable third-century A.D. “Jonah sarcophagus,” that includes a peacock holding Jonah’s gourd in its claws. Even for readers who do not know this background, however, the magnificent peacock feather hints at the transformation Jonah has undergone inside the whale.

Chocheli’s illustrations are rich and beautiful. They do not so much represent the Jonah story as highlight core images and themes in an open-ended way, inviting readers to linger and wonder over the story. Adults as well as children should find them rewarding.

3. Exegesis

Since the text of this book is taken directly from the Biblical book of Jonah, I have less to comment on exegetically. But it is worth briefly considering how this book handles the issue of Old Testament typology. Typology refers to the way in which Old Testament figures and events become symbols of later ones. Thus the Sabbath is a type of the age to come, or the temple is a type of Christ’s body. Typology is central to patristic and thus to Orthodox scriptural interpretation, and it is a theme of some of Chocheli’s other children’s books.

Jonah is one of the clearest Christological types since the connection is drawn by Jesus himself:

As Jonah was in the belly of the whale, so will the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth. The people of Ninevah will arise at the Judgment with this generation and condemn it; for they repented at the preaching of Jonah, and behold, something greater than Jonah is here. (Matthew 12:40-42; cf. Luke 11:29-32)

In a brief introduction to Chocheli’s The Book of Jonah, Father Thomas Hopko, Dean of St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Seminary, reminds parents of these Christological overtones. But he immediately cautions against overdoing it. The power of Jonah, he says, lies rather in the narrative itself and the grace of God that works through it:

The prophecy of Jonah needs no special commentary. Explanations of its multiple meaning often tend to ruin it. The inspired parable needs only to be read with our children, who adore it as it is. Its prophetic proclamation and messianic message will, by God’s grace, reveal itself to our souls.

There is wisdom in this counsel. If Christ is anticipated in the Old Testament, it is not as though the Old Testament is a code to be cracked. Rather, the coherence of Jesus’ story with the Old Testament is primarily a literary coherence, like the deep coherence of a great novel. On one level this is a matter of narrative succession. Jesus’ life is what it is because it continues the story of Israel’s exodus and its law, its kings and its prophets. On another level, the Old Testament defines the linguistic and moral world in which alone the story of Jesus makes sense. Jesus’ words and deeds as rabbi and prophet, Son of Man and Son of God, would make little sense (even an unexpected sense) except in the context of this broader world.

But we speak about typology because there is yet a deeper symbolic kind of coherence. Noteworthy characters or events can produces “echoes” later in the story, echoes which are not necessary but are all the same fitting and appropriate. Typology is an aesthetic phenomenon, the discernment of a gratuitous coherence that adds beauty to the Biblical story. For just this reason, typology is the sort of aesthetic phenomenon that is often best left to do its work behind the scenes of the mind.

This is the course Chocheli has wisely chosen. After this brief introduction, The Book of Jonah makes no explicit reference to Jesus. Likewise, in his illustrations, Chocheli handles typology with a very light touch. Besides the intimation of resurrection in the peacock feather, the only other hint of the Jonah-Christ typology that I can discern is a cross placed subtly but distinctly behind Jonah as he is vomited out of the whale. An attentive child will probably notice the cross and ask why it’s there, opening a conversation about Jonah’s experience as an anticipation of Christ’s death and resurrection. Chocheli does not impose this type on the reader, however, but leaves us instead to draw it out in conversation. Like the book of Jonah itself, Chocheli’s illustrations speak directly and openly about Jonah, and only indirectly and very obscurely about Christ.

4. Conclusion

The Book of Jonah is not easy; but then, neither is the Bible. Chocheli’s version combines a remarkable deference to the Bible’s way of telling Jonah’s story with exquisite and suggestive artwork that will spark the imaginations of adults as well as children. This is one of my favorite versions of Jonah. I highly recommend it! 👍

If after reading this review you’re interested in buying this book, please consider supporting my work by using the Amazon affiliate links on this page.

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Hi Mark! Hope you are well. I re-found your children's book reviews in preparation for my nephew's upcoming baptism. If you pick up this series again, some candidate books for review: Tomie de Paola's collections and the Lego Brick Bibles.