Yesterday I gave my first sermon at my new parish, St. Alban’s DC. I focused on the intriguing figure of Lydia, whom Paul meets “outside the gates” of Philippi. I take this meeting-place as a clue to the sort of person Lydia is: a woman outside. Give it a read or a listen and tell me what you think.

In the sermon I compare Lydia to the remarkable founder of St. Alban’s: Phoebe Nourse. Her story is told in the first chapter of a detailed (and compelling) history of St. Alban’s called The Church at the Crossroads. It was written by one of our parishioners, Ruth Cline, after a lot of painstaking archival research. As you’ll see, my account draws heavily on hers. I don’t want my sermons to be academic essays, cluttered with footnotes; but I should have recognized Cline and her book by name from the pulpit. At least I can do so here.

It’s wonderful to be here with you this morning, my second Sunday as your new assistant rector. I’m grateful for the warm welcome that you all gave me and my family last week. We are so excited to be joining this thriving community!

During the season of Easter, our readings speak of the risen life of Christ as it grows and bears fruit in the church, which means that they speak constantly of the Holy Spirit who is the giver of this life. Eastertide ends in a few weeks with Pentecost; but the whole Easter season is already Pentecostal.

In today’s reading from John [14:23-29], we look back to the Holy Spirit’s source: it is a gift of the Father, bringing the wisdom, peace, and courage embodied by Christ. In Revelation [21:10, 22-22:5], we look ahead to the completion of the Spirit’s work, when all creation will be infused with the life of God. And our reading from Acts [16:9-15] shows us the Spirit at work in the present: calling and forbidding, giving visions and meeting needs, opening hearts and transforming lives.

As I’m beginning a new ministry here among you, the question of God’s calling is at the top of my mind. So I’d like to focus this morning on our reading from Acts.

The Spirit’s Calling

Acts is the second of two volumes attributed to Luke. It picks up where the gospel of Luke leaves off, telling how the Spirit of the risen Christ brings the earliest church into being through the acts of the apostles, especially Peter and Paul.

In our reading, Paul and his companions have set out on a second missionary journey, intending to build on their first mission by expanding into the provinces of Asia and Bithynia (roughly, Western Turkey). But the Holy Spirit keeps stopping them, diverting them first to Galatia and Phrygia (in central Turkey) and then to the port city of Troas. There, Paul has a vision of “a man from Macedonia pleading with him and saying, ‘Come over to Macedonia and help us” (16:9). Paul and his companions promptly set sail for the port city of Neapolis (in modern Greece), and then travel inland to Philippi.

As someone who has spent a number of years now discerning God’s call on my life, I’m struck by the many and various ways that the Spirit uses to call Paul to Macedonia. As at other decisive moments in the book of Acts,1 the Spirit may speak in ways that are miraculous and manifest: Paul has a vision. But the Spirit also guides Paul through ordinary human prudence and planning. In going to Macedonia, Paul is answering a plea for help, rooted in an identifiable need. In entering Philippi, Paul is executing a definite strategy, focused on planting churches in major cities.

And the Spirit also gets Paul to Macedonia by preventing him from going somewhere else. Our text is opaque about how exactly the Spirit keeps Paul out of Asia and Bithynia; and we might suppose that here again the Spirit uses miraculous means: a powerful inner conviction, perhaps, or a prophetic word.

But my guess is that the text is opaque because the Spirit’s voice was opaque, whispered in the quiet but emphatic language of facts. Perhaps intense opposition from local authorities made it impossible to enter Asia. Or, perhaps Paul set out full of confident plans and schemes – and then hit a wall because everything went disastrously awry. Or perhaps Paul suffered some kind of illness. Verse 10 is the first time Luke uses the first person plural, “we,” to describe Paul’s adventures; and Luke was a physician. Perhaps Luke joined their party at Troas because he was asked to treat Paul’s illness.2

However they got there, I wonder what Paul was thinking as he sat in Troas with his companions, nothing to show for weeks or months of effort. Was he brimming with optimism, still confident that the Spirit was at work? Or did he feel like a failure, a stubborn fool?

The Spirit still directs our paths in these many and various ways. I first explored a call to the priesthood in my 20s in the UK, after working for several years as a youth pastor in Azerbaijan. But I came to feel that the time wasn’t right; I wasn’t prepared to commit to life in England, and I was still burdened with big questions that required academic study to answer. By the time I’d finished my Ph.D., my plans had changed: I wanted to be a professor. But I kept hitting a wall – or perhaps I should say, with our text, that the Spirit of Jesus did not allow it. I did teach religion for five grueling years in New York City, earning a pittance and never finding enough time to study and write. Then the pandemic hit, we moved here to DC, and I found myself a stay-at-home dad to our son. This was not the plan, but it was the need; and to my surprise, I loved it. I realized that being a father involves many of the things I had loved about ministry: teaching, forming, caring. I came to see that the Spirit was calling me to the priesthood after all, and eventually, to you!

I didn’t get a miraculous vision; and there were days when I felt like a failure, or a stubborn fool. But I see now that the Holy Spirit was at work, at least as much in failure as when things went according to plan.

A Woman “Outside the Gate”

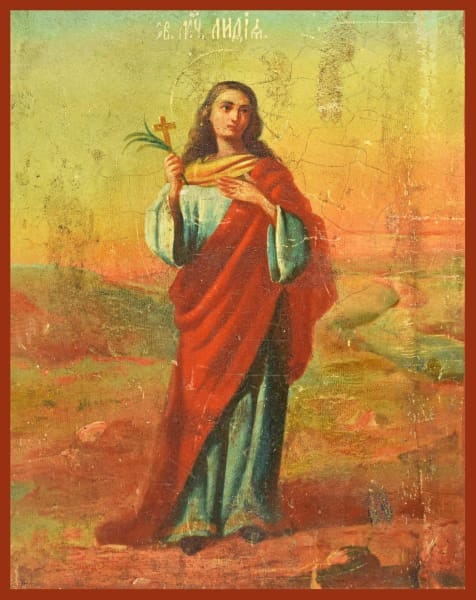

Enough about me. In our reading, the Spirit was not only at work in the apostle Paul. He was also working in the life of the intriguing figure of Lydia, a lay leader in the church of Philippi and the so-called “first convert in Europe.”3

I’m struck by where Paul meets Lydia: “outside the gate” of the city (16:13). Paul’s custom upon entering a new city was to begin by preaching in the local synagogue. But apparently there was no synagogue in Philippi, or none that would give Paul a hearing. The closest Paul can find is this Sabbath gathering of women by the river, “outside the gate.”

The fact that Paul meets Lydia here is a clue to the kind of woman she is. She is a woman outside – out of step, out of the ordinary, out of place.

Lydia is “outside the gate” because she is a foreigner. She lives in Philippi, but she comes from the city of Thyatira (16:14), in the region of Lydia. Her very name marks her as foreign: “Lydia” is a nickname that means “the woman from Lydia,” the way we might call a Texan “Tex.” Ironically, Thyatira is in Asia – for in God’s divine sense of humor, the first convert in Europe was an immigrant from the very region that the Spirit had just forbidden Paul to visit! Perhaps it is because Lydia lives outside her home city, in a culture not her own, that she proves so open to the message of these foreign men with their strange new teaching.

The little gathering of Christians that met in Lydia’s home in Philippi may have been a little like St. Alban’s. For as an intentionally bilingual community, we too are committed to the often difficult work of building bridges between different cultures. We want to be a home for those at ease in the language and culture of Washington, and for those who feel like “strangers in a strange land” (Exodus 2:22). May our community be a sign of God’s kingdom, which does not belong to one people or ethnic group, but to “every tongue, tribe, and nation” (Revelation 7:9).

Lydia is also “outside the gate” in matters of religion. For she is a “worshipper of God” (16:14), a Gentile worshipping the God of Israel, probably without converting to Judaism. She had taken the conscious step of setting herself outside the pagan world of her ancestors, with their violent, wanton, all too-human gods. But as a Gentile dabbling in Jewish practice, she probably did not feel quite at home in the Jewish community either. Like Lydia, the early church as a whole was awkwardly positioned between Judaism and Gentile paganism, neither the one nor the other, but some emerging third thing that proved puzzling to most, threatening to some.

At its best, I think our Anglican tradition has been similar. We’re a via media, a middle way between Catholicism and Protestantism – not a lukewarm compromise or incoherent blend, but a living and compelling third way. Today our society is so often divided into opposed tribes fighting zero-sum battles. Perhaps the church needs more people like Lydia, more people with this very Anglican ability to be neither the one nor the other, but a third thing.

Lydia is also “outside the gate” that kept Greco-Roman women in their place, relegated to the domestic sphere. Lydia was a powerful woman in a man’s world. Her hometown of Thyatira was known for its expensive purple dyes, and she herself was “a dealer in purple cloth” (16:14). As a result, she was apparently a woman of means, with resources enough to host Paul and his companions during their time in Philippi. She operates as the head of her household, with authority to open her home to Paul and to see that the whole household is baptized (v. 15).

Lydia must have been something like Phoebe Nourse, the founder of St. Alban’s. Phoebe Nourse was a “woman of quiet determination,” with a vision of the first “free church” here in DC, a church whose pews would be “open to all.”4 Over many years, she sold her needlework and saved the money to make this church a reality. Upon her death in 1850, a beautiful obituary described her as a sort of outsider to the world. If you ask “the votaries of vanity and Fashion and folly” about her, it says, “they would all say:--We did not know her, she was not one of us.” But ask her Pastor, ask the Sunday School teachers, ask the students about her: “every ancient and infirm and poor man and woman and child of whatever color will tell you, she visited us, she clothed us, she fed us, she often stood by our bed-side and cheered and comforted us.”5 Lydia, I think, had a similar spirit; and may it be so of us.

Faithfulness

We meet Lydia “outside the gate”: a foreigner, a religious outsider, a strong woman – out of step, out of the ordinary, out of place.

But do not misunderstand me. We have no reason to think that Lydia herself was particularly concerned one way or the other about her “identity” as a Lydian or a Philippian, as a woman, as a Gentile worshipper of a Jewish God. There is no hint that she made a point of being an outsider for its own sake: a counter-cultural rebel or a disruptive provocateur.

If she is a woman outside, this is a byproduct of something more fundamental about her. Lydia gets only one line in the book of Acts, one sentence to sum up her character. She says to Paul: “If you have judged me to be faithful to the Lord, come and stay at my home” (v. 15). At issue is not her identity, her social status, her cultural style. Her only question is: am I faithful to the Lord?

She asks Paul to know her by her loyalties, by the way her deeds and her character show that the Lord is the God and center of her life.

And she is faithful. She is faithful in prayer and in Sabbath-keeping: for Paul first meets her among a group of women praying on the Sabbath. She is faithful in listening and learning: the text twice observes that she “listened” to Paul and his message. She is faithful in hospitality and generosity: for she insists on opening her home to these strangers for the sake of the gospel.

Those who are faithful to the Lord will often find themselves, with Lydia, outside the gates, out of step, out of the ordinary – but being outside is a byproduct, not an end in itself. Being faithful to the Lord is the main thing, the only thing, because our end is God: a strange God who meets us outside the gates of heaven, in the human life of Jesus Christ and in the Spirit who shares Christ’s divine life with us even now.

Let us be known by our loyalties. Let us be known as faithful to the Lord, like Lydia, like Phoebe Nourse. Let us prove faithful in prayer, in learning, in generosity, in all the works of God’s Spirit, who is at work among us. May the Spirit open our hearts, as he opened Lydia’s heart, and make us faithful to the risen Lord, who alone is worthy of our loyalty. Amen.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Particularly Paul’s conversion (Acts 9:1-19) and Peter’s vision of the sheet (Acts 10:9-16).

Some commentators suggest that this could be the very “physical infirmity” which, according to Galatians 4:13, first brought him to Galatia.

In Orthodox tradition, she is also given the honorific “equal to the apostles.”

I’m quoting and paraphrasing Ruth Cline here, who wrote: “She was a young woman of quiet determination and purpose. By selling her fine needlework and setting aside small sums, she started a fund to found a ‘free’ church on Mount Alban that she intended to be open to all.” (Church at the Crossroads, p. 5).

The whole obituary can be found in Ruth Cline, Church at the Crossroads, p. 17.

This is a very cool take on Lydia - her story changed my story. 🙏🏽💜