I delivered this sermon last Sunday, March 16th, 2025, at St. Paul’s K Street. The text was Genesis 15:1-12, 17-18, in which God makes the so-called “covenant of the pieces” with Abram. Unfortunately, no recording was made so you’ll have to settle for the written word.

I had intended to give a heady sermon about the Pauline doctrine of justification by faith, focused on the text “Abram believed the Lord, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness,” but the Spirit directed me instead to God’s word of comfort to Abram: “Do not fear! I am your shield; your reward shall be very great.” These are uncertain times; I hope these words will be some comfort to you as well.

I can’t resist sharing this fantastic kids’ song about this passage by the band Slugs and Bugs. Somehow it is instructive, a little silly, and singable all at the same time. “Bring me a heifer…”

I would like to reflect today on our Old Testament reading, which tells of a strange encounter between God and Abram, early in Abram’s story. “Do not be afraid, Abram,” God says. “I am your shield; your reward shall be very great.” (Gen. 15:1)

If God says this to Abram, he must need to hear it: he must be afraid. One reason we read his story, and all the scriptures, is because they hold up a mirror to our shared human condition. We are not the first to feel our hearts gripped by fear; we are not the first to live through uncertain times. Human life is fleeting and fragile, and so scripture is full of fearful things: failure and barrenness, malice and betrayal, economic downturn and political upheaval–suffering and death.

God’s word speaks to us in our fear, always the same message: do not be afraid. Do not shrink back, do not give in to cowardice. Be bold, be strong, be courageous, for you are not alone: the God who creates all things, the God of mercy and love, this God is with you. This was God’s word to Hagar, desperate and alone (Gen. 21:17); to the wilderness generation, who felt “like grasshoppers in their own eyes” (Deut. 20:3; Num. 13:33) to the people of Judea, exiled in Babylon (Isaiah 43:5 et al.); to Mary, at the annunciation of a very unplanned pregnancy (Luke 1:30).

And it is God’s word to Abram: “Do not be afraid, Abram. I am your shield. Your reward shall be very great!”

Abram has just returned victorious from a daring nighttime raid to rescue his nephew Lot from a coalition of Canaanite kings. He receives a blessing from the mysterious Melchizedek, “priest of God Most High” (Gen. 14:18). He also meets the king of Sodom and refuses to accept any share in the spoils of war, lest that wicked king say, “I have made Abram rich” (Gen. 14:23).

It’s “after these things,” (Gen. 15:1) we are told, that God says to Abram, “do not be afraid.” Why now? Some suggest that he fears another attack from the defeated Canaanites. When God says, “I am your shield,” he means: I will protect you from your enemies. Perhaps he is also anxious about his financial prospects, having refused the riches of war. When God says, “your reward shall be very great,” he means: you will prosper without this tainted wealth.

But these are small fears compared to the grave dangers he has already faced. Was it not frightening when Abram left his country and his family and his father’s house to go to an unknown land? When he faced famine and fled to Egypt? When he entered the fray against the Canaanite kings?

Why now, why in this moment of victory, does Abram need to hear “do not be afraid”?

I suspect that Abram’s fear was a deeper kind of fear: not the fear of suffering, or of losing what he has, but the fear that what he has might be all there is.

Abram’s is the existential fear that we may experience when we contemplate our own mortality. Abram is old, and old age has a way of putting things in perspective. It can teach us by experience what Ash Wednesday reminds us in symbol and ritual: you are dust, and to dust you shall return. But that means that our victories, as well as our defeats, will come to nothing.

Abram is anxious about the very meaning and purpose of his life. What was the point of risking everything to come to Canaan? What have I really gained through my victories? What blessing can God give that won’t soon become dust? This is why Abram pushes back against God’s word of comfort. “What reward can you give me, for I continue childless!” (Gen. 15:2) What Abram wants – what God has promised him – is a lineage, descendents, a people; and not just any people, but one committed to the divine project entrusted to Abram. He wants to father “a great nation” (Gen. 12:2), a nation whose greatness consists in being a blessing to all (Gen. 12:3). Without an heir, he reasons, this project will die with him.

Abram is afraid that his life will count for nothing. This explains the text’s strange remark that “Abram believed the LORD, and the LORD reckoned it to him as righteousness” (Gen. 12:6). The word “righteousness” is a metaphor of measuring or judging. In Hebrew, accurate weights and measures are called “righteous,” as is a person vindicated in a court of law. But we can also, as it were, measure a whole human life: was it worth living? Was it rightly lived? Scripture sometimes imagines a divine court of judgment after death, where our lives will be measured by the One who alone knows their true worth. Someone is “righteous,” whom, we suppose, God will vindicate on that day, whose life will be proved right and meaningful.

We remember Abram because, when this fear threatened, he did not shrink back but continued with courage into God’s future. Abram knew the antidote to fear: “Abram believed the LORD” (Gen. 15:6). Abram had faith – not just a spiritual yearning, or a sense that “religious community” is an important part of a full life. No, Abram staked everything on his conviction that this God would do the specific things he had promised, despite all appearances to the contrary.

At his advanced age and without a child of his own, this must have been the “great reward” for which he hoped against hope: that God would bless him and bless the nations through him, multiply his offspring and make them a great nation devoted to this project of blessing. But these things could not come to fruition until long after Abram’s death. If they are Abram’s reward, it is a reward he can only enjoy by faith, which is a strange kind of reward.

But the phrase “I am your shield; your reward shall be very great” could also be translated: “I am your shield, [I am] your very great reward.” On this reading, the great reward is God himself, God’s presence with Abram by faith, now and in the future, whatever his circumstances. By faith, this was the great reward of the Hebrew people, whether wandering in the wilderness, settled in the land, or scattered among the nations. By faith, this is our great reward in Christ. In good times and in bad, in joy and in suffering, we can dwell with the God who holds our future in his hands; and being with God can make our faith in God more firm and our hope for his promised future more secure.

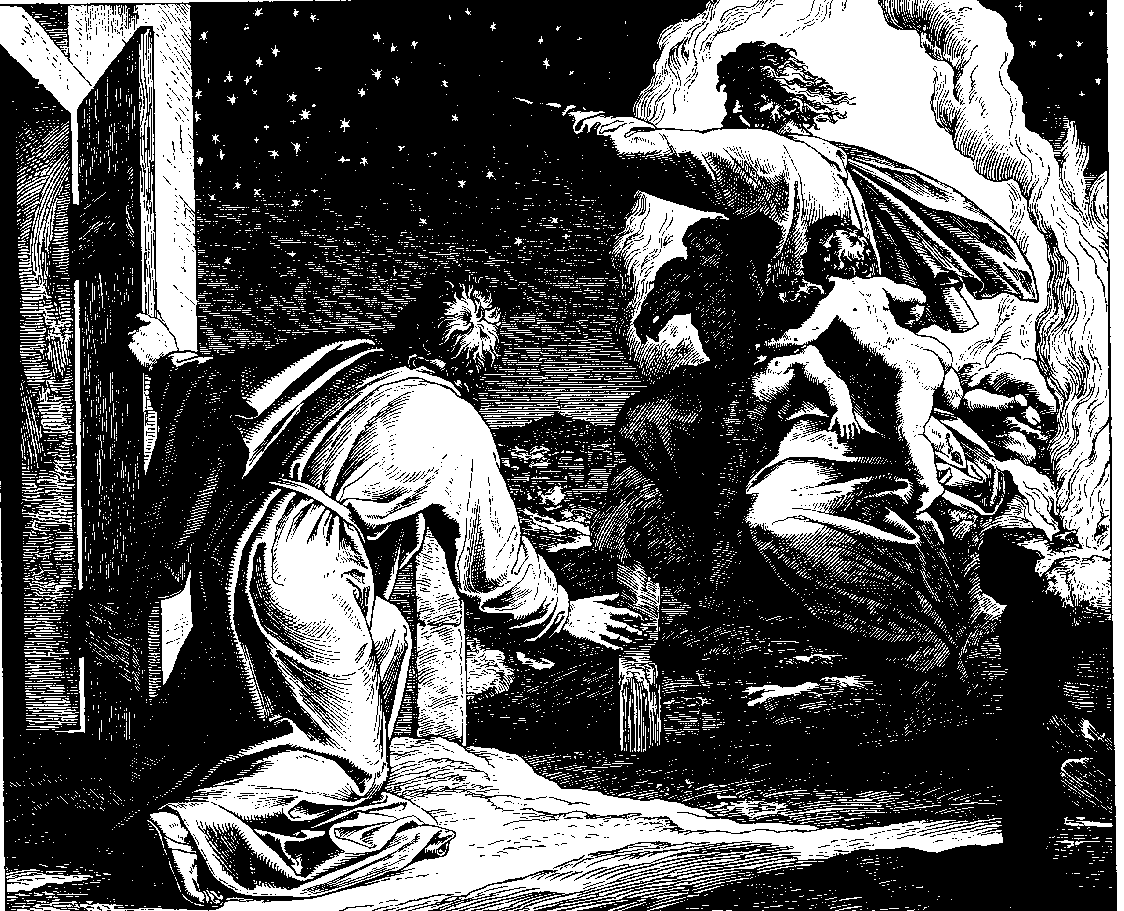

This is why our passage ends with another strange encounter between God and Abram (Gen. 15:9-20). At God’s command, Abram cuts up animals and positions the pieces across from one another in two rows; then he falls into a deep sleep. Our lectionary skips the troubling word that God speaks to Abram: his descendants will not inherit the land of Canaan any time soon, and only after being enslaved for centuries in Egypt (Gen. 15:13-16).

But after dimly revealing this frightful future, there in the darkness, God makes a covenant with Abram. It was the custom in those days to ratify a covenant by passing between broken animals, ritually invoking a curse upon oneself: “may the same happen to me if I break this covenant.” Abram, you will notice, never passes through the pieces; he commits to nothing. Only “a smoking fire pot and a flaming torch” pass through (Gen. 15:17), objects of smoke and fire that must represent God himself, who is a consuming fire (Deut. 4:24), and dwells in thick darkness (1 Kings 8:12). God shows his presence to Abram simply to secure the blessings he has already promised, with no strings attached. This covenant is not a contract, in which both parties take on obligations to the other. Its blessings are given by grace, not by works.

There is something almost sacramental about this encounter. From one point of view, there is nothing new here – God has already promised these things to Abram. But through this ritual and its physical objects, God and his Word of blessing become present to Abram and more intimately bound to him. The covenant is ratified by God in flesh, and sealed (in chapter 17) in Abram’s flesh in the “sacrament” of circumcision. By passing through these broken bodies, God even hints that, if it were possible, he would rather that his own body be broken than that his blessings be withheld from Abram and his children.

For we are children of Abram’s faith; his faith is the pattern of our own. When fear of death and anxiety about life threatened, Abram trusted God because he believed (however vaguely) that God brings life and blessings that are greater even than death. He trusted that his withered body and Sarah’s barren womb might yet bring forth a child; and what is this, but life out of death?

We know that this life has now been realized, though in a way Abram could never have imagined. His descendants did settle in the land of promise; and from that land, through one of those descendants, Jesus Christ, who died and who rose from the dead, never to die again, God’s blessings to Abram were poured out upon all the world.

There is also a difference between Abram’s faith and ours. For him, what it means to walk in faith with God, and exactly what blessings God promises, remained quite vague. Only much later — through the Law — does it become clear to Abram’s family just how much trusting in this God means walking in his ways by loving others, pursuing justice, becoming holy. For us in light of Christ, it has become even clearer that to have faith in God is to entrust ourselves to one whose blessings are love, joy, peace, patience, and the like. These things are the true blessings of resurrection life.

We live in uncertain times; there is much to fear. And there is always Abram’s great fear, the fear of all fears, that whether we fail or succeed, lose or gain, suffer or rejoice – death brings all of it to dust.

But we who share Abram’s fears may also share in his blessings. God’s covenant with Abram includes us; and so God’s word to Abram is also his word to us: “Do not be afraid. I am your shield and your very great reward.” God does not promise to keep us from suffering, any more than he kept Abram’s children from slavery. God does not spare us from the trial of death, any more than he spared Jesus the cross.

But even so, do not be afraid: in Christ’s broken body, God has made with us, as he made with Abram, an unbreakable covenant of grace. Do not be afraid: in Christ we have God himself as our shield, we receive God’s Spirit as our very great reward. Do not be afraid: we have become part of Abram’s great nation, with whom God shares his highest blessings – not power or wealth or territory, but the things of Christ: love, joy, peace, justice. Do not be afraid: Christ is really present with us at this altar, in the broken body we eat and the blood that we drink, strengthening our faith in Abram’s God of promise. Do not be afraid, for God is with us.

Amen.